Recently I was asked to do some homework to prepare for an interview on Linux kernel internals, and I was given the following to analyse:

Specifically, we would like you to study and be able to discuss the code path that is exercised when a kernel caller allocates an object from the kernel memory allocator using a call of the form:

object = kmalloc(sizeof(*object), GFP_KERNEL);For this discussion, assume that (a) sizeof(*object) is 128, (b) there is no process context associated with the allocation, and (c) we’re referencing an Ubuntu 4.4 series kernel, as found at

git://kernel.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/ubuntu-xenial.git

In addition, we will discuss the overall architecture of the SLUB allocator and memory management in the kernel, and the specifics of the slab_alloc_node() function in mm/slub.c.

I spent quite a lot of time, maybe 8-10 hours, studying how the SLUB memory allocator functions, and looking at the implementation of kmalloc(). It’s a pretty interesting process, and it is well worth writing up.

Let’s get started, and I will try to keep this simple.

Virtual Memory Principles

On devices which run operating systems, the kernel is in charge of managing hardware, scheduling processes and managing memory. On basic or older operating systems, when a process is loaded into memory, it might be placed in the same place every time, and uses actual hardware addresses.

This is fine for extremely basic systems, like rudimentary embedded systems, but this quickly becomes a problem on more complex systems which need to run multiple processes at a time.

Suddenly you cannot load multiple programs because they may require use of the same addresses, or you run into problems where segmentation is not respected and the user space program decides to overrun and start using addresses reserved for the kernel.

This is all fixed by virtual memory.

On most systems, virtual memory is implemented via paging. Basically, physical memory is divided into small sections, called pages. On normal Intel x86 processors, a page is 4kb / 4096b in size.

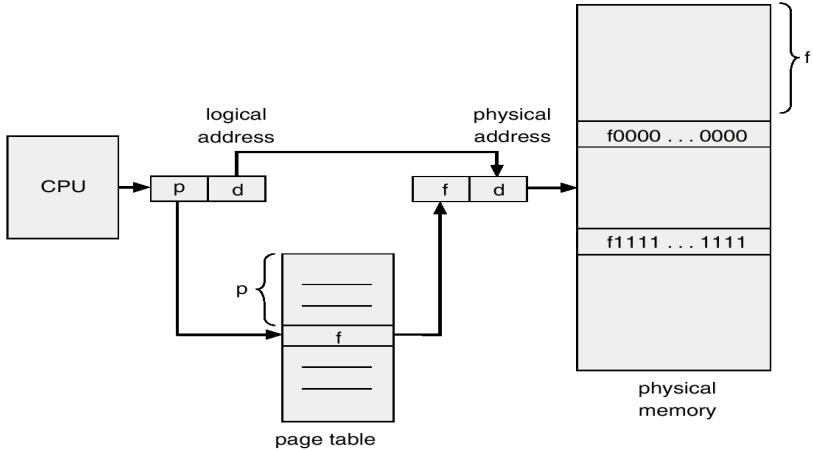

Virtual memory is implemented by creating a mapping between virtual addresses and physical addresses, and storing that mapping in page tables.

Now when you start a process, pages are allocated for its memory. The process sees the virtual addresses, and they might start at a specific address, such as 0x0001000, if the application requires it. The nice thing is, we can now load multiple programs into memory, and give them the same addresses if they require it, since the first might map virtual address 0x000139A to physical address 0x07F739A, and another process might map virtual address 0x000139A to 0x043539A.

The translation is done with a linear page table:

Now, you might imagine that constantly looking up addresses in the page table might have a performance penalty, and you would be right.

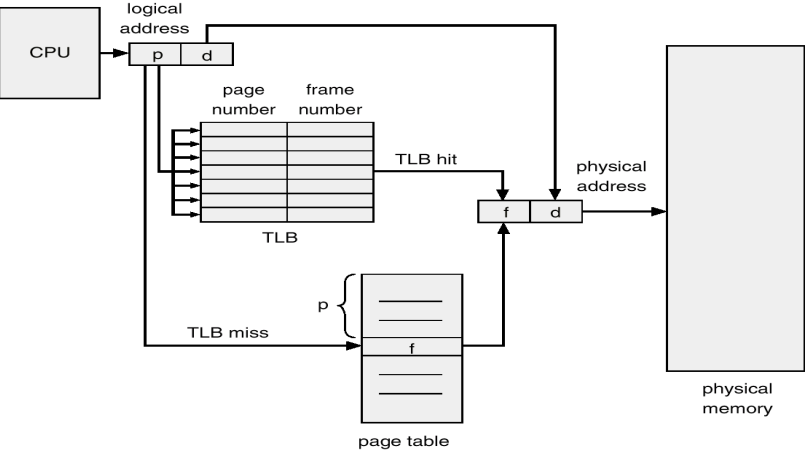

Most modern computers use a Translation Lookaside Buffer which is a cache of recently used virtual addresses. This is implemented in hardware and is quite fast.

Great. So now, when the kernel needs to allocate memory, it finds some empty pages, and places a new entry in the page table, and returns a virtual address to the requester.

This works great for large blocks of memory, since the kernel will try and allocate pages which are contiguous in memory, keeping read and write times lower.

But what happens if we don’t want to allocate large amounts of memory. What happens if we want small bits of memory, like smaller than a page (4096b)?

This is what the homework is about. What happens when we allocate say, 128b?

The SLOB Allocator

The SLOB (Simple List Of Blocks) allocator is on of the three big memory allocators in the Linux kernel. It is primarily used in small embedded systems where memory is expensive, and SLOB on a whole, uses very little memory in its implementation.

It works by using a first-fit type of algorithm.

This is where it places the object in the first possible place in memory which it will fit. If the space is not big enough, it keeps linearly going through memory until it finds a spot.

Now, the problem with this allocator is that it can pretty quickly lead to fragmentation, where there are many small empty slots between occupied slots, but they are not large enough to place larger, newly requested objects.

The primary issues is that we are trying to store objects of different sizes in the same places, and when we free some objects, there is no standardised sized place for new objects.

The SLAB Allocator

The SLAB allocator fixes all the shortcomings of SLOB, and then some. It was used as the default memory allocator in the Linux kernel until version 2.6.23, when SLUB took over.

The SLAB allocator works around the idea that allocating memory for objects and freeing memory for objects in the kernel is a very common thing to do, and the act of creating them from scratch and then removing them takes more time than simply allocating the memory.

So, the SLAB allocator sets up a pool of pre-allocated objects of various sizes. Objects of the same size are grouped together and placed in “slabs”. Slabs normally span across many contiguous memory pages, in order to give a good pool to draw from. The objects are all allocated during boot time, where time spent on allocation does not really matter.

There is quite a large overhead involved with keeping these slabs around, since you need a slab for each particular object size, and you also need a slab queue per cpu. This means that SLAB is not all that ideal on systems where memory is limited, like hand-held gaming consoles or embedded systems.

SLAB also has to keep track of significant amounts of metadata for each slab, which also adds to the overhead.

The general process for SLAB is this:

- The kernel is asked for memory for an object of size x

- The SLAB allocator looks in the slab index for the slab that holds objects of size x

- The SLAB allocator gets a pointer to the slab where objects are stored

- The SLAB allocator finds the first place with an empty slot

- The SLAB allocator returns the address of the empty slot, with some housekeeping to do on the side.

A similar process is used for freeing memory, namely, marking the slot as unused.

Now, SLAB had some scalability problems, and is best put by the creator of SLUB, Christoph Lameter:

SLAB Object queues exist per node, per CPU. The alien cache queue even has a queue array that contain a queue for each processor on each node.

For very large systems the number of queues and the number of objects that may be caught in those queues grows exponentially.

On our systems with 1k nodes / processors we have several gigabytes just tied up for storing references to objects for those queues

This does not include the objects that could be on those queues.

One fears that the whole memory of the machine could one day be consumed by those queues.

It appears that SLAB works fine for small workloads such as personal computers, but not for supercomputers.

The SLUB Allocator

SLUB was designed by Christoph Lameter, as a drop in replacement for the SLAB allocator, as it conforms to the same API. It is the default memory allocator in the Linux kernel.

It keeps to the same inner principles as SLAB, but it drops the requirements of complex queues and per slab metadata. Instead, it greatly simplifies things by only storing information about the locations of each slab, and for each slab, where to find the next free object.

Information about all active slabs are kept in a list in the kmem_cache structure. Per-slab metadata is kept to three basic fields in struct page, and are:

void *freelist;

short unsigned int inuse;

short unsigned int offset;

freelist is a pointer to the first available object inside a slab, inuse is a counter which keeps track of the number of objects being used, and offset is the offset to the next free object. This can be calculated by

next_object = freelist + offset;

When inuse is 0, it means that all objects are not being used, and if necessary, the slab can be freed and the pages returned back to the system if memory gets low.

SLUB is also useful because it can merge slabs together, in order to keep memory overheads low. Objects of similar sizes can be placed in the same slabs, which reduces the amount of slabs you need to allocate at the beginning.

Debugging is also already built into SLUB whether you enable it or not, and if something strange happens during runtime, there are facilities already available to help you debug potential misbehaving slabs. There are poison zones and red zones between objects which are set to fixed values, so if an object has too much data written to it, the red zone will be damaged, and the mistake obvious.

The Implementation of kmalloc()

Okay, that is probably enough theory and architecture. Let’s have a look at the implementation.

Remember that the homework was for the call:

object = kmalloc(128, GFP_KERNEL);

kmalloc() is the recommended function to call when you want to allocate an object which is smaller than a page.

kmalloc() is defined in /include/linux/slab.h:446

static __always_inline void *kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags)

{

if (__builtin_constant_p(size)) {

if (size > KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE)

return kmalloc_large(size, flags);

#ifndef CONFIG_SLOB

if (!(flags & GFP_DMA)) {

int index = kmalloc_index(size);

if (!index)

return ZERO_SIZE_PTR;

return kmem_cache_alloc_trace(kmalloc_caches[index],

flags, size);

}

#endif

}

return __kmalloc(size, flags);

}

kmalloc() takes in two parameters, size and flags. size is how large the object we are allocating memory for is, and flags are access conditions.

We will talk more about flags later.

The first condition checks to see if the size variable is a constant which the compiler can see at compile time. 128b is not, so we jump straight to the function call __kmalloc(size, flags) at the bottom.

__kmalloc() is defined in /mm/slub.c:3519

void *__kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags)

{

struct kmem_cache *s;

void *ret;

if (unlikely(size > KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE))

return kmalloc_large(size, flags);

s = kmalloc_slab(size, flags);

if (unlikely(ZERO_OR_NULL_PTR(s)))

return s;

ret = slab_alloc(s, flags, _RET_IP_);

trace_kmalloc(_RET_IP_, ret, size, s->size, flags);

kasan_kmalloc(s, ret, size);

return ret;

}

The struct kmem_cache contains a list of the active slabs, and ret will be the object that we will be returning.

The first thing that happens, is size is compared with KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE. KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE is defined in /include/linux/slab.h, and is defined as:

...

#ifdef CONFIG_SLUB

...

#define KMALLOC_SHIFT_HIGH (PAGE_SHIFT + 1)

...

#endif

...

#define KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE (1UL << KMALLOC_SHIFT_HIGH)

Now, PAGE_SHIFT is 12, since 1 << 12 = 4096, which makes PAGE_SHIFT + 1 = 13. 1 << 13 is 8192, which is the size of two pages.

kmalloc() is only meant to be called for object sizes of less than one page, but if called with sizes larger than two pages, then it calls kmalloc_large().

In our case, 128b is nowhere near 8192b, so we head into kmalloc_slab().

kmalloc_slab() is defined in /mm/slab_common.c:851

struct kmem_cache *kmalloc_slab(size_t size, gfp_t flags)

{

int index;

if (unlikely(size > KMALLOC_MAX_SIZE)) {

WARN_ON_ONCE(!(flags & __GFP_NOWARN));

return NULL;

}

if (size <= 192) {

if (!size)

return ZERO_SIZE_PTR;

index = size_index[size_index_elem(size)];

} else

index = fls(size - 1);

#ifdef CONFIG_ZONE_DMA

if (unlikely((flags & GFP_DMA)))

return kmalloc_dma_caches[index];

#endif

return kmalloc_caches[index];

}

Again there is a sanity check for too large objects, and now something interesting happens. If the object size is less than 192b, we look it up in size_index table at position size_index_elem(size).

size_index_elem() is fairly simple:

static inline int size_index_elem(size_t bytes)

{

return (bytes - 1) / 8;

}

(128 - 1) / 8 = 15, noting that we return an integer. So for objects of size 128, their slab index is stored at position 15 in the size_index table.

static s8 size_index[24] = {

3, /* 8 */

4, /* 16 */

5, /* 24 */

5, /* 32 */

6, /* 40 */

6, /* 48 */

6, /* 56 */

6, /* 64 */

1, /* 72 */

1, /* 80 */

1, /* 88 */

1, /* 96 */

7, /* 104 */

7, /* 112 */

7, /* 120 */

7, /* 128 */

2, /* 136 */

2, /* 144 */

2, /* 152 */

2, /* 160 */

2, /* 168 */

2, /* 176 */

2, /* 184 */

2 /* 192 */

};

The 15th position reveals 7. Objects of size 128 are stored in the 7th slab. We return a pointer to the slab with the final line:

return kmalloc_caches[index]

Moving on. __kmalloc() does a quick sanity check with the pointer to ensure it is not 0, and we move onto the next interesting call, ret = slab_alloc(s, flags, _RET_IP_);.

Note: _RET_IP_ is a GCC builtin to access the return address of the current stack frame.

slab_alloc() is defined in /mm/slub.c:2569

static __always_inline void *slab_alloc(struct kmem_cache *s,

gfp_t gfpflags, unsigned long addr)

{

return slab_alloc_node(s, gfpflags, NUMA_NO_NODE, addr);

}

Here we pick up another variable NUMA_NO_NODE, which applies to Non-Uniform Memory Access cells.

Now we get to the real action. Let’s call slab_alloc_node().

Analysis of slab_alloc_node()

slab_alloc_node() is defined in /mm/slub.c:2482

I won’t place the entire function here because it is quite long, and we want to analyse it section by section.

static __always_inline void *slab_alloc_node(struct kmem_cache *s,

gfp_t gfpflags, int node, unsigned long addr)

{

void *object;

struct kmem_cache_cpu *c;

struct page *page;

unsigned long tid;

s = slab_pre_alloc_hook(s, gfpflags);

if (!s)

return NULL;

...

For the moment, we will ignore the variable declarations. They will become important soon, but not yet.

For now, we are interested in slab_pre_alloc_hook().

slab_pre_alloc_hook() is defined in /mm/slub.c:1282

static inline struct kmem_cache *slab_pre_alloc_hook(struct kmem_cache *s,

gfp_t flags)

{

flags &= gfp_allowed_mask;

lockdep_trace_alloc(flags);

might_sleep_if(gfpflags_allow_blocking(flags));

if (should_failslab(s->object_size, flags, s->flags))

return NULL;

return memcg_kmem_get_cache(s, flags);

}

We first mask the gfp flags with all allowed bits to make sure nothing untoward gets set.

The next interesting part is the calls: might_sleep_if(gfpflags_allow_blocking(flags));.

gfpflags_allow_blocking() is defined in /include/linux/gfp.h:272

static inline bool gfpflags_allow_blocking(const gfp_t gfp_flags)

{

return (bool __force)(gfp_flags & __GFP_DIRECT_RECLAIM);

}

We return true if the provided gfp_flag has __GFP_DIRECT_RECLAIM set. Time to see what the flag which we were given, GFP_KERNEL sets.

...

#define __GFP_DIRECT_RECLAIM ((__force gfp_t)___GFP_DIRECT_RECLAIM) /* Caller can reclaim */

#define __GFP_RECLAIM ((__force gfp_t)(___GFP_DIRECT_RECLAIM|___GFP_KSWAPD_RECLAIM))

...

#define GFP_KERNEL (__GFP_RECLAIM | __GFP_IO | __GFP_FS)

And there we have it. GFP_KERNEL sets __GFP_RECLAIM, which sets ___GFP_DIRECT_RECLAIM and another value via bitwise or. Which means gfpflags_allow_blocking() will return true.

Looking at might_sleep_if(), defined in /include/linux/kernel.h

#ifdef CONFIG_PREEMPT_VOLUNTARY

extern int _cond_resched(void);

# define might_resched() _cond_resched()

#else

...

#endif

...

#ifdef CONFIG_DEBUG_ATOMIC_SLEEP

...

else

...

# define might_sleep() do { might_resched(); } while (0)

# define sched_annotate_sleep() do { } while (0)

#endif

...

#define might_sleep_if(cond) do { if (cond) might_sleep(); } while (0)

We see that might_sleep_if() eventually maps to _cond_resched().

This is quite important, since it means that a call to kmalloc() with the GFP_KERNEL flag set can potentially sleep.

Sleeping may be required since a page might need to be fetched, and this might take some time, so if we sleep, we can give up our processor to another task, and we can be woken back up once the page has arrived.

Continuing on, the next interesting part of slab_pre_alloc_hook() is the last line, the return statement:

return memcg_kmem_get_cache(s, flags);

This goes to the memory control group and acquires the slab we will be working on.

Back to slab_alloc_node(). The next section is this:

redo:

/*

* Must read kmem_cache cpu data via this cpu ptr. Preemption is

* enabled. We may switch back and forth between cpus while

* reading from one cpu area. That does not matter as long

* as we end up on the original cpu again when doing the cmpxchg.

*

* We should guarantee that tid and kmem_cache are retrieved on

* the same cpu. It could be different if CONFIG_PREEMPT so we need

* to check if it is matched or not.

*/

do {

tid = this_cpu_read(s->cpu_slab->tid);

c = raw_cpu_ptr(s->cpu_slab);

} while (IS_ENABLED(CONFIG_PREEMPT) &&

unlikely(tid != READ_ONCE(c->tid)));

We read the cpu tid and then obtain a raw pointer to the cpu.

The tid is a unique transaction number, defined as such:

#ifdef CONFIG_PREEMPT

/*

* Calculate the next globally unique transaction for disambiguiation

* during cmpxchg. The transactions start with the cpu number and are then

* incremented by CONFIG_NR_CPUS.

*/

#define TID_STEP roundup_pow_of_two(CONFIG_NR_CPUS)

#else

/*

* No preemption supported therefore also no need to check for

* different cpus.

*/

#define TID_STEP 1

#endif

Each cpu has a tid initialised to the CPU number, and with each transaction, is incremented by CONFIG_NR_CPUS, which keeps tid numbers unique.

Afterwards, we start a loop where if pre-emption is enabled, we check to see if the tid we read still matches the tid from the cpu pointer we just got.

Why? Well. If CONFIG_PREEMPT is enabled, it means that kernel code can be pre-empted, which means that an interrupt can occur, and we start executing code in another part of the kernel instead.

This check is in place to ensure that while we were pre-empted, if it did at all happen, that another thread on the cpu did not also call slab_alloc_node(). If it did, then the tid, which acts as a unique number, will be different. If that happens, we simply re-read the tid and cpu pointer.

/*

* Irqless object alloc/free algorithm used here depends on sequence

* of fetching cpu_slab's data. tid should be fetched before anything

* on c to guarantee that object and page associated with previous tid

* won't be used with current tid. If we fetch tid first, object and

* page could be one associated with next tid and our alloc/free

* request will be failed. In this case, we will retry. So, no problem.

*/

barrier();

This is reinforced in the comment above. barrier() is called to ensure that the reads occur in the correct order.

object = c->freelist;

page = c->page;

if (unlikely(!object || !node_match(page, node))) {

object = __slab_alloc(s, gfpflags, node, addr, c);

stat(s, ALLOC_SLOWPATH);

} else {

void *next_object = get_freepointer_safe(s, object);

object will be set to the first object on the freelist linked list. We do a quick sanity check here to ensure that object is not a NULL pointer, in which case there would be no slots free on this slab. If that happens, we would then have to call __slab_alloc() to go through the process to decide to allocate a completely new slab, or to borrow slabs from other cpus.

Assuming there are slots free in the lab, we take the false patch, with a call to get_freepointer_safe().

static inline void *get_freepointer_safe(struct kmem_cache *s, void *object)

{

void *p;

#ifdef CONFIG_DEBUG_PAGEALLOC

probe_kernel_read(&p, (void **)(object + s->offset), sizeof(p));

#else

p = get_freepointer(s, object);

#endif

return p;

}

This calls get_freepointer():

static inline void *get_freepointer(struct kmem_cache *s, void *object)

{

return *(void **)(object + s->offset);

}

This makes sense, since the next_object is determined by the pointer to the current object plus an offset. The same offset declared in struct page for this particular slab.

Now comes the tricky part of slab_alloc_node().

/*

* The cmpxchg will only match if there was no additional

* operation and if we are on the right processor.

*

* The cmpxchg does the following atomically (without lock

* semantics!)

* 1. Relocate first pointer to the current per cpu area.

* 2. Verify that tid and freelist have not been changed

* 3. If they were not changed replace tid and freelist

*

* Since this is without lock semantics the protection is only

* against code executing on this cpu *not* from access by

* other cpus.

*/

if (unlikely(!this_cpu_cmpxchg_double(

s->cpu_slab->freelist, s->cpu_slab->tid,

object, tid,

next_object, next_tid(tid)))) {

note_cmpxchg_failure("slab_alloc", s, tid);

goto redo;

}

A cmpxchg instruction is performed. What happens here, is that we check to make sure that the freelist pointer and the tid have not been changed, and we do this by comparing the previously read object and tid variables.

If they are the same, then the freelist and tid are updated to their new values of next_object and next_tid().

next_tid() is defined as such:

static inline unsigned long next_tid(unsigned long tid)

{

return tid + TID_STEP;

}

tid is incremented by the next TID_STEP, which is CONFIG_NR_CPUS.

This cmpxchg actions happens atomically, and enforced by the cpu. Because of this, there does not need to be any locking involved.

The cmpxchg is necessary due to a feature of SLUB. If a cpu finds that their slab is full, instead of allocating a completly new slab, __slab_alloc() will first attempt to borrow a partial slab from another cpu instead. If this happens, then the freelist will be modified and the tid will not match. In this case, cmpxchg will fail, and we take the goto redo; path.

Continuing on, we come to the bottom part of slab_alloc_node():

prefetch_freepointer(s, next_object);

stat(s, ALLOC_FASTPATH);

}

if (unlikely(gfpflags & __GFP_ZERO) && object)

memset(object, 0, s->object_size);

slab_post_alloc_hook(s, gfpflags, 1, &object);

return object;

}

Next, we have a call to prefetch_freepointer():

static void prefetch_freepointer(const struct kmem_cache *s, void *object)

{

prefetch(object + s->offset);

}

What prefetch() does is begin the process of fetching the next free object and sticking it in the cache lines. This is to speed up access later on in slab_post_alloc_hook().

Another interesting thing is that if the __GFP_ZERO flag is set, then the object is zeroed out through a call to memset(). I imagine this is how kcalloc() is implemented.

Next up is a call to slab_post_alloc_hook():

static inline void slab_post_alloc_hook(struct kmem_cache *s, gfp_t flags,

size_t size, void **p)

{

size_t i;

flags &= gfp_allowed_mask;

for (i = 0; i < size; i++) {

void *object = p[i];

kmemcheck_slab_alloc(s, flags, object, slab_ksize(s));

kmemleak_alloc_recursive(object, s->object_size, 1,

s->flags, flags);

kasan_slab_alloc(s, object);

}

memcg_kmem_put_cache(s);

}

The most important part here is the call to memcg_kmem_put_cache() which returns the modified slab to the memory control group.

Finally we ride return object; all the way up through the call stack, and return it to the caller of kmalloc().

The object is now ready to use.

Finishing Up

That is a general overview of what happens when kmalloc() is called. It requires a surprising amount of theory to be able to understand its implementation, and even then, the implementation is quite tricky to understand fully.

I was surprised by the complexity of kernel memory allocators, but in the end I suppose it all makes perfect sense.

Being able to pre-allocate objects of fixed sizes and then offer up available objects to callers is much less work than allocating individual objects on demand. SLUB is a great part of the Linux kernel.

I learned quite a lot about memory management in the Linux kernel studying up for this homework. I’m happy I did it, as now /mm isn’t as scary as it was before.

Hope you liked the read!

Matthew Ruffell